Geometry

Geometrically, the swastika can be regarded as an irregular icosagon or 20-sided polygon. The proportions of the Nazi swastika were fixed based on a 5 × 5 diagonal grid.[5]

Characteristic is the 90° rotational symmetry and chirality, hence the absence of reflectional symmetry, and the existence of two versions of swastikas that are each other's mirror image.

|

|

|

|

A right-facing swastika might be described as "clockwise" or "counter-clockwise".

|

The mirror-image forms are often described as:

- clockwise and anti-clockwise;

- left-facing and right-facing;

- left-hand and right-hand.

"Left-facing" and "right-facing" are used mostly consistently referring to the upper arm of an upright swastika facing either to the viewer's left (卍) or right (卐). The other two descriptions are ambiguous as it is unclear whether they refer to the arms as leading or being dragged or whether their bending is viewed outward or inward. However, "clockwise" usually refers to the "right-facing" swastika. The terms are used inconsistently in modern times, which is confusing and may obfuscate an important point, that the rotation of the swastika may have symbolic relevance, although ancient vedic scripts describe the symbolic relevance of clock motion and counter clock motion.[citation needed] Less ambiguous terms might be "clockwise-pointing" and "counterclockwise-pointing."

Nazi ensigns had a through and through image, so both versions were present, one on each side, but the Nazi flag on land was right-facing on both sides and at a 45° rotation.[6]

The name "sauwastika" is sometimes given to the left-facing form of the swastika (卍).[7]

[edit] Origin hypotheses

Among the earliest cultures utilizing swastika is the neolithic Vinča culture of South-East Europe (see Vinča symbols).

More extensive use of the Swastika can be traced to Ancient India, during the Indus Valley Civilazation.

The swastika is a repeating design, created by the edges of the reeds in a square basket-weave. Other theories attempt to establish a connection via cultural diffusion or an explanation along the lines of Carl Jung's collective unconscious.

The genesis of the swastika symbol is often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of pagan Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems emerging in the Neolithic,[8] nothing certain is known about the symbol's origin. There are nevertheless a number of speculative hypotheses. One hypothesis is that the cross symbols and the swastika share a common origin in simply symbolizing the sun. Another hypothesis is that the 4 arms of the cross represent 4 aspects of nature - the sun, wind, water, soil. Some have said the 4 arms of cross are four seasons, where the division for 90-degree sections correspond to the solstices and equinoxes. The Hindus represent it as the Universe in our own spiral galaxy in the fore finger of Lord Vishnu. This carries most significance in establishing the creation of the Universe and the arms as 'kal' or time, a calendar that is seen to be more advanced than the lunar calendar (symbolized by the lunar crescent common to Islam) where the seasons drift from calendar year to calendar year. The luni-solar solution for correcting season drift was to intercalate an extra month in certain years to restore the lunar cycle to the solar-season cycle. The Star of David is thought to originate as a symbol of that calendar system, where the two overlapping triangles are seen to form a partition of 12 sections around the perimeter with a 13th section in the middle, representing the 12 and sometimes 13 months to a year. As such, the Christian cross, Jewish hexagram star and the Muslim crescent moon are seen to have their origins in different views regarding which calendar system is preferred for marking holy days. Groups in higher latitudes experience the seasons more strongly, offering more advantage to the calendar represented by the swastika/cross.

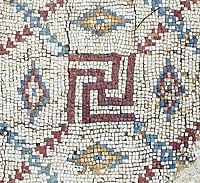

Mosaic swastika in excavated Byzantine(?) church in

Shavei Tzion (Israel)

Carl Sagan in his book Comet (1985) reproduces Han period Chinese manuscript (the Book of Silk, 2nd century BC) that shows comet tail varieties: most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it, recalling a swastika. Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.[9] Bob Kobres in Comets and the Bronze Age Collapse (1992) contends that the swastika like comet on the Han Dynasty silk comet atlas was labeled a "long tailed pheasant star" (Di-Xing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or track. Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside China.

In Life's Other Secret (1999), Ian Stewart suggests the ubiquitous swastika pattern arises when parallel waves of neural activity sweep across the visual cortex during states of altered consciousness, producing a swirling swastika-like image, due to the way quadrants in the field of vision are mapped to opposite areas in the brain.[10]

Alexander Cunningham suggested that the Buddhist use of the shape arose from a combination of Brahmi characters abbreviating the words su astí.[3]

[edit] Archaeological record

The earliest swastika known has been found from Mezine, Ukraine. It is carved on late paleolithic figurine of mammoth ivory, being dated as early as about 10,000 BC. It has been suggested this swastika is a stylized picture of a stork in flight.[11]

In India, Bronze Age swastika symbols were found at Lothal and Harappa, on Indus Valley seals.[12] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[13] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiabang,[14] Dawenkou and Xiaoheyan cultures.[15] Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks and Germanic peoples and Slavs.

The swastika is also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between AD300-600.

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[16]) is a characteristic motive in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[17] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motive, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed, to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[18

]