Atop a barge on Wednesday, June 6, 2012, the space shuttle Enterprise was towed on the Hudson River past the Statue of Liberty on its way to the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, where it will be permanently displayed.Image Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

Learn about Venus's weird transit cycle.

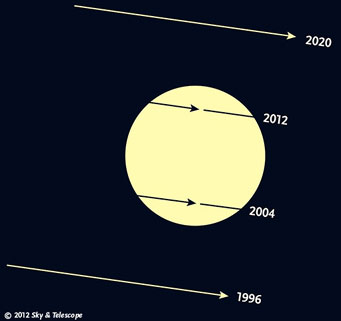

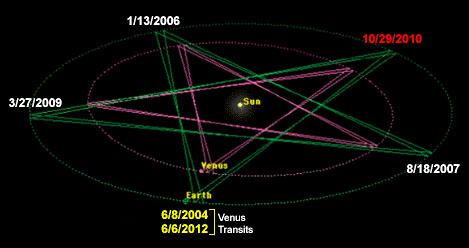

Venus took these tracks across the Sun in 2004 and 2012. Earth missed seeing a transit in 1996, and will miss another in 2020.

S&T: Gregg Dinderman

People attuned to the rhythms of the night sky know that certain cycles in astronomy repeat themselves over and over. These include the annual seasonal cycle as Earth orbits the Sun, the 29½-day cycle of lunar phases, and the fact that Mars comes to opposition every 26 months. Even solar and lunar eclipses come in saros cycles.

But compared to these other cycles, the current cycle for transits of Venus is weird. Make that really weird. This article explains why transits of Venus are so rare that the transit coming up on June 5th/6th will be the last one you'll ever see, why the cycle has such an odd pattern, and why the current cycle won't last forever. (The transit occurs on June 5th in the Western Hemisphere and June 6th in the Eastern Hemisphere.)

How to Get a Transit of Venus

For a transit of Venus to occur, two events must occur simultaneously, and it's rare to have such perfect synchrony.

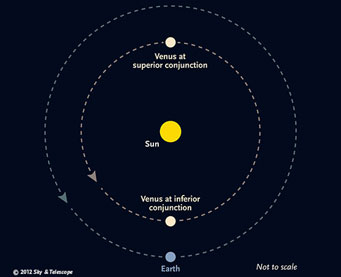

Transits of Venus can only occur when Venus passes between the Sun and Earth, a point on its orbit known as inferior conjunction.

S&T

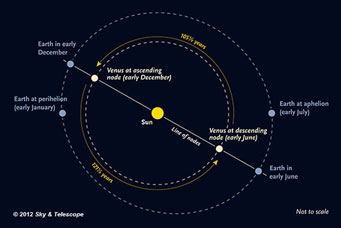

First, and most obvious, Venus has to move directly between Earth and the Sun so that an imaginary observer looking “down” on the solar system from above would see the three bodies form a perfectly straight line. When this happens, astronomers say that Venus has come to inferior conjunction. Venus orbits the Sun faster and in a smaller orbit, and it comes to these inferior conjunctions every 584 Earth days.

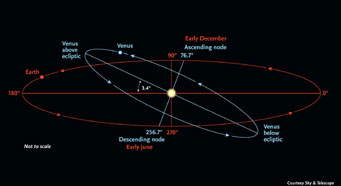

If Venus and Earth orbited the Sun in the same plane, we'd enjoy a transit of Venus every 584 days, and the June 5th transit wouldn't be such a big deal. But in reality, Venus's orbital plane is tipped 3.4 degrees relative to Earth's orbital plane. The planes cross each other at two points called nodes. To get a transit, Venus has to be at inferior conjunction at the exact same time it's at a node. This perfect 3-D lineup doesn't happen very often. Normally, Venus's inclined orbit means it is located “above” or “below” the Sun when it comes to inferior conjunction.

Venus's orbit around the Sun is inclined relative to Earth's orbit (exaggerated here for the sake of clarity). Transits of Venus can only occur at the two nodes, where the orbital planes of Venus and Earth intersect.

S&T: Gregg Dinderman

One of these nodes occurs in early June and the other in early December, meaning these are the only times that transits of Venus can occur. In early June, Venus appears to be diving “downward” (or south), so astronomers call this the descending node. In early December, Venus is moving “up” (or north) in its orbit, so this is an ascending node.

A Bizarre Cycle

So far, things probably seem rather simple and straightforward. But here's where the transit of Venus cycle starts getting weird (but also quite interesting).

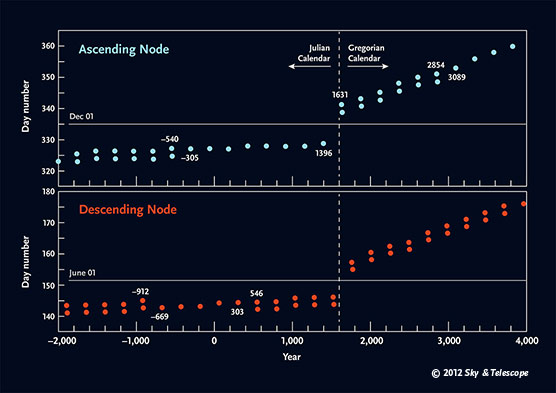

For the past few centuries and the next few centuries, these perfect 3-D alignments occur at intervals of 8, 105½, 8, and 121½ years. In reality, think of this as a 243-year cycle, with pairs of transits separated by only 8 years, but with each pair separated by more than a century.

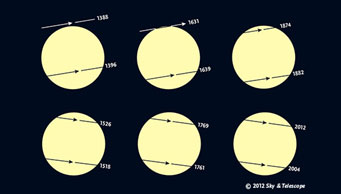

Venus tracks across the Sun are shown for years 1388 through 2012. The top row shows December transits at Venus's ascending node and the bottom row shows June transits at Venus's descending node.

S&T

Ascending-node transits occurred in December 1631, 1639, 1874, and 1882. The next ones occur in December 2117 and 2125. Descending-node transits occurred in June 1761, 1769, and 2004, with the next one coming June 5/6, 2012. After that, the next descending-node transits occur in June 2247 and 2255.

For the descending-node transits separated by 8 years, Venus crosses the southern part of the Sun's disk in the first transit, and the northern part the second time around. That's why Venus will cross the northern part of the Sun's disk on June 5th/6th. When Venus came to inferior conjunction in 1996, it was too far below the Sun to transit its disk. And in 2020, it will be too high.

The opposite is the case for ascending-node transits. The first transit in an 8-year pair crosses the northern part of the Sun, the second one crosses the southern half.

So why does Venus take “only” 105½ years to go from a pair of June transits to a pair of December transits, whereas it takes 121½ years to go from a pair of December transits to a pair of June transits? This asymmetry is due to the fact that Earth's orbit around the Sun is not quite a perfect circle. It's slightly elongated (the technical term is eccentric), deviating from a perfect circle by about 3 percent. In contrast, Venus's orbit is so close to being a perfect circle that its minuscule elongation can be ignored in this discussion.

The Earth's elongated (eccentric) orbit (exaggerated in the diagram) explains why there is an asymmetry in the amount of time from one transit pair to the next.

S&T

The diagram on the right (in which Earth's orbital eccentricity is exaggerated for the sake of clarity) shows what's going on. Basically, Earth is near its farthest point from the Sun (aphelion) in June and near its closest point to the Sun (perihelion) in December. When Earth is closer to the Sun's powerful gravity, it moves slightly faster in its orbit than when it's farther from the Sun. The difference in Earth's orbital speed from perihelion to aphelion produces a longer gap (121½ years) between the time it takes to line up between the December and Junes transits than the 105½ years it takes to line up from the June to December transits.

Nothing Good Lasts Forever

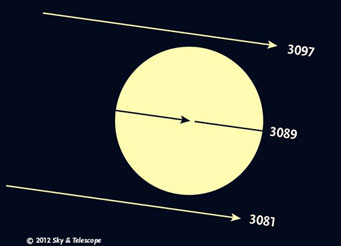

In the future, transits of Venus will become even more rare. This diagram shows the track Venus will take across the Sun in 3089. In 3081 and 3097, Venus's path will miss the Sun (from Earth's perspective).

S&T

Unfortunately for astronomers living in the distant future, the frequency of transits will decrease. Both Venus's and Earth's orbits precess, meaning they rotate over long time periods to produce a rosette-like pattern. In other words, Earth's perihelion shifts in its orbit, and so does Venus's. Because of precession, Earth-bound astronomers will only be able to enjoy one ascending-node transit for centuries after the year 3000. They will see a descending-node transit in 3089, but 8 years later, in 3097, Venus will come to inferior conjunction too far above the Sun to transit its disk.

And over tens of thousands of years, the 243-year cycle will eventually change as the eccentricity of Venus's and Earth's orbits evolve due to the gravitational perturbations of other planets. Over even longer timescales, chaotic effects take over, and the mathematics becomes so uncertain that today's astronomers can no longer predict when these rare celestial alignments will take place, and what future cycles will be like.

But for now, you can rest assured that there will be a transit of Venus on June 5th/6th, and unless modern medicine comes up with a miracle, this will be the last chance you'll ever have to see a transit of Venus from the surface of Earth.

By plotting the number of days into each year when a transit of Venus occurs, it's easy to see the long-term behavior of transits of Venus, and the fact that we're fortunate to live during a period when we get to see two transits at both the ascending and descending nodes. Note the change from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar around the year 1600. Retired NASA astronomer Fred Espenak provided S&T with the data for this diagram.

Courtesy Sky & Telescope

6

6