| At 12:06:34 UTC 29 March 2025 (update) |

| Format | Decimal time | Zone |

| French |

5h 11m 5s |

Paris MT |

| Fraction |

0.50456 d |

GMT/UTC |

| Swatch .beats |

@546 |

BMT/CET |

Times are in different time zones.

French decimal clock from the time of the

French Revolution. The large dial shows the ten hours of the decimal day in

Arabic numerals, while the small dial shows the two 12-hour periods of the standard 24-hour day in

Roman numerals.

Decimal time is the representation of the time of day using units which are decimally related. This term is often used specifically to refer to the French Republican calendar time system used in France from 1794 to 1800, during the French Revolution, which divided the day into 10 decimal hours, each decimal hour into 100 decimal minutes and each decimal minute into 100 decimal seconds (100,000 decimal seconds per day), as opposed to the more familiar standard time, which divides the day into 24 hours, each hour into 60 minutes and each minute into 60 seconds (86,400 SI seconds per day).

The main advantage of a decimal time system is that, since the base used to divide the time is the same as the one used to represent it, the representation of hours, minutes and seconds can be handled as a unified value. Therefore, it becomes simpler to interpret a timestamp and to perform conversions. For instance, 1h23m45s is 1 decimal hour, 23 decimal minutes, and 45 decimal seconds, or 1.2345 decimal hours, or 123.45 decimal minutes or 12345 decimal seconds; 3 hours is 300 minutes or 30,000 seconds. This property also makes it straightforward to represent a timestamp as a fractional day, so that 2025-03-29.54321 can be interpreted as five decimal hours, 43 decimal minutes and 21 decimal seconds after the start of that day, or a fraction of 0.54321 (54.321%) through that day (which is shortly after traditional 13:00). It also adjusts well to digital time representation using epochs, in that the internal time representation can be used directly both for computation and for user-facing display.

Paper dial to convert a 12-hour clock face to decimal time, presented to the Revolutionary Committee of Public Instruction by Hanin.

| decimal | 24-hour | 12-hour |

| 0:00 |

00:00 |

12:00 a.m. |

| 1:00 |

02:24 |

2:24 a.m. |

| 2:00 |

04:48 |

4:48 a.m. |

| 3:00 |

07:12 |

7:12 a.m. |

| 4:00 |

09:36 |

9:36 a.m. |

| 5:00 |

12:00 |

12:00 p.m. |

| 6:00 |

14:24 |

2:24 p.m. |

| 7:00 |

16:48 |

4:48 p.m. |

| 8:00 |

19:12 |

7:12 p.m. |

| 9:00 |

21:36 |

9:36 p.m. |

The decans are 36 groups of stars (small constellations) used in the ancient Egyptian astronomy to conveniently divide the 360 degree ecliptic into 36 parts of 10 degrees. Because a new decan also appears heliacally every ten days (that is, every ten days, a new decanic star group reappears in the eastern sky at dawn right before the Sun rises, after a period of being obscured by the Sun's light), the ancient Greeks called them dekanoi (δεκανοί; pl. of δεκανός dekanos) or "tens". A ten-day period between the rising of two consecutive decans is a decade. There were 36 decades (36 × 10 = 360 days), plus five added days to compose the 365 days of a solar based year.

Decimal time was used in China throughout most of its history alongside duodecimal time. The midnight-to-midnight day was divided both into 12 double hours (traditional Chinese: 時辰; simplified Chinese: 时辰; pinyin: shí chén) and also into 10 shi / 100 ke (Chinese: 刻; pinyin: kè) by the 1st millennium BC.[1][2] Other numbers of ke per day were used during three short periods: 120 ke from 5 to 3 BC, 96 ke from 507 to 544 CE, and 108 ke from 544 to 565. Several of the roughly 50 Chinese calendars also divided each ke into 100 fen, although others divided each ke into 60 fen. In 1280, the Shoushi (Season Granting) calendar further subdivided each fen into 100 miao, creating a complete decimal time system of 100 ke, 100 fen and 100 miao.[3] Chinese decimal time ceased to be used in 1645 when the Shíxiàn calendar, based on European astronomy and brought to China by the Jesuits, adopted 96 ke per day alongside 12 double hours, making each ke exactly one-quarter hour.[4]

Gēng (更) is a time signal given by drum or gong. The character for gēng 更, literally meaning "rotation" or "watch", comes from the rotation of watchmen sounding these signals. The first gēng theoretically comes at sundown, but was standardized to fall at 19:12. The time between each gēng is 1⁄10 of a day, making a gēng 2.4 hours long (2 hours 24 minutes). As a 10-part system, the gēng are strongly associated with the 10 celestial stems, especially since the stems are used to count off the gēng during the night in Chinese literature.

As early as the Bronze-Age Xia dynasty, days were grouped into ten-day weeks known as xún (旬). Months consisted of three xún. The first 10 days were the early xún (上旬), the middle 10 the mid xún (中旬), and the last nine or 10 days were the late xún (下旬). Japan adopted this pattern, with 10-day-weeks known as jun (旬). In Korea, they were known as sun (순,旬).

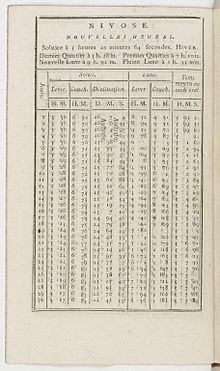

Astronomical table from the Almanach national de France using decimal time

In 1754, Jean le Rond d'Alembert wrote in the Encyclopédie:

- It would be very desirable that all divisions, for example of the livre, the sou, the toise, the day, the hour, etc. would be from tens into tens. This division would result in much easier and more convenient calculations and would be very preferable to the arbitrary division of the livre into twenty sous, of the sou into twelve deniers, of the day into twenty-four hours, the hour into sixty minutes, etc.[5][6]

In 1788, Claude Boniface Collignon proposed dividing the day into 10 hours or 1,000 minutes, each new hour into 100 minutes, each new minute into 1,000 seconds, and each new second into 1,000 tierces (older French for "third"). The distance the twilight zone travels in one such tierce at the equator, which would be one-billionth of the circumference of the earth, would be a new unit of length, provisionally called a half-handbreadth, equal to four modern centimetres. Further, the new tierce would be divided into 1,000 quatierces, which he called "microscopic points of time". He also suggested a week of 10 days and dividing the year into 10 "solar months".[7]

Decimal time was officially introduced during the French Revolution. Jean-Charles de Borda made a proposal for decimal time on 5 November 1792. The National Convention issued a decree on 5 October 1793, to which the underlined words were added on 24 November 1793 (4 Frimaire of the Year II):

- VIII. Each month is divided into three equal parts, of ten days each, which are called décades...

- XI. The day, from midnight to midnight, is divided into ten parts or hours, each part into ten others, so on until the smallest measurable portion of the duration. The hundredth part of the hour is called decimal minute; the hundredth part of the minute is called decimal second. This article will not be required for the public records, until from the 1st of Vendémiaire, the year three of the Republic. (September 22, 1794) (emphasis in original)

Thus, midnight was called dix heures ("ten hours"), noon was called cinq heures ("five hours"), etc.

3 different representations of 3 hours 86 minutes decimal time by Delambre (9:15:50 a.m.)

The colon (:) was not yet in use as a unit separator for standard times, and is used for non-decimal bases. The French decimal separator is the comma (,), while the period (.), or "point", is used in English. Units were either written out in full, or abbreviated. Thus, five hours eighty three minutes decimal might be written as 5 h. 83 m. Even today, "h" is commonly used in France to separate hours and minutes of 24-hour time, instead of a colon, such as 14h00. Midnight was represented in civil records as "ten hours". Times between midnight and the first decimal hour were written without hours, so 1:00 am, or 0.41 decimal hours, was written as "four décimes" or "forty-one minutes". 2:00 am (0.8333) was written as "eight décimes", "eighty-three minutes", or even "eighty-three minutes thirty-three seconds".

As with duodecimal time, decimal time was represented according to true solar time, rather than mean time, with noon being marked when the sun reached its highest point locally, which varied at different locations, and throughout the year.

In "Methods to find the Leap Years of the French Calendar", Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre used three different representations for the same decimal time:

- 0,386 (comma is the decimal sign in French)

- 0j386 ("j" is for jour, day in French)

- 3h 86' (apostrophe is for minutes)

Marriage certificate for Napoleon's sister, dated 12 floreal l'An V "à Sept heures Cinq Decimes" (May 1, 1797, at 6:00 pm).

Sometimes in official records, decimal hours were divided into tenths, or décimes, instead of minutes. One décime is equal to 10 decimal minutes, which is nearly equal to a quarter-hour (15 minutes) in standard time. Thus, "five hours two décimes" equals 5.2 decimal hours, roughly 12:30 p.m. in standard time.[8][9] One hundredth of a decimal second was a decimal tierce.[10]

Although clocks and watches were produced with faces showing both standard time with numbers 1–24 and decimal time with numbers 1–10, decimal time never caught on; it was not used for public records until the beginning of the Republican year III, 22 September 1794, and mandatory use was suspended 7 April 1795 (18 Germinal of the Year III). In spite of this, decimal time was used in many cities, including Marseille and Toulouse, where a decimal clock with just an hour hand was on the front of the Capitole for five years.[11] In some places, decimal time was used to record certificates of births, marriages, and deaths until the end of Year VIII (September 1800). On the Palace of the Tuileries in Paris, two of the four clock faces displayed decimal time until at least 1801.[12] The mathematician and astronomer Pierre-Simon Laplace had a decimal watch made for him, and used decimal time in his work, in the form of fractional days.

Decimal time was part of a larger attempt at decimalisation in revolutionary France (which also included decimalisation of currency and metrication) and was introduced as part of the French Republican Calendar, which, in addition to decimally dividing the day, divided the month into three décades of 10 days each; this calendar was abolished at the end of 1805. The start of each year was determined according to the day of the autumnal equinox, in relation to true or apparent solar time at the Paris Observatory.