iv. On the Wolf Trail

The Blackfoot tribe of the Rocky Mountains believe that the sky-world, inhabited by a celestial race of people, is reached via something called the Wolf Trail, which turns out to be the Milky Way.

It forms part of a foundation story that is arguably Palaeolithic in origin, and might easily have crossed over to North America from the Eurasian continent more than 11,500 years ago.

A number of other tribes preserve similar traditions about the Milky Way, seen as a celestial road or river to the sky-world. More significantly, some tribes, such as the Skidi Pawnee, single out the sky-world as a Star of the North, often confused with Polaris, the current Pole Star, which is nowhere near the Milky Way.

This northerly-placed star is associated by the Skidi Pawnee and others, with a constellation known as the Bird Foot, or Turkey Foot, a three-pronged device identified as Cygnus, making Deneb the most likely candidate for the Star of the North. Such knowledge is confirmation that ancient star-lore of this nature might well date back to when Deneb was Pole Star. It also strengthens the case for such ideas being inherited by the Early Neolithic peoples from their Palaeolithic ancestors.

Yet what was the continuity of this veneration of Cygnus among the Native American tribes? Could its significance be taken back to the age of the Hopewell mound builders of the Ohio Valley, who were one of the earliest cultures known to have emerged on the North American continent? One example is an enormous circular earthwork known as Great Circle in Newark, Ohio. At its centre is a bird, or bird foot, shaped earthwork called Eagle Mound, thought to have been constructed by the Hopewell culture in c. 100 BC.

The henge monument's single entrance faces the point on the horizon where the midsummer sunrise occurs, and after surveying the site we find that it was constructed so that anyone watching from Eagle Mound prior to sunrise on the summer solstice would have seen the Milky Way rising up into the sky from between the site's entrance.

If the celestial trial was followed upwards it would take the observer to where the stars of Cygnus were to be seen directly overhead, imitating the position of Eagle Mound.

Thus Eagle Mound was almost certainly a representation of Cygnus as the Bird Foot constellation, an opinion drawn already by at least one archaeo-astronomer, Thaddeus M Cowan, who has identified Newark's Eagle Mound, as well as other bird effigy mounds constructed by the Hopewell, with the Cygnus constellation.

The purpose of the midsummer alignment was most probably to enable the living and the dead to access the sky-world via the Milky Way as the celestial road or river of the soul.

Back to Contents

v. Maya Cosmogenesis

Was the same interest in Cygnus to be found in other parts of the American continent? Archaeologist Marion Popenoe Hatch excavated the Olmec site of La Venta, in the Tabasco province, at the beginning of the 1970s and determined that the site's fluted pyramid, built c. 1000 BC, was aligned towards the stars of both Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) and Sadr (gamma Cygni) the central star in Cygnus, these were used in conjunction with each other to determine the time of the summer solstice, a tradition she traces back to 2000 BC.

The symbol in Mayan texts used to represent Cygnus she has identified as the cross bands glyph, which appears also on much earlier Olmec statues of the were-jaguar. This, she suspects, signifies the starry sky.

Cygnus can be seen as a key constellation in Olmec and Mayan astronomy, a point previously unrecognized by everyone but Popenoe Hatch.

It features also as the beautiful bird Seven Macaw, who sits atop the World Tree in Maya tradition. This can easily be interpreted as the Milky Way, as is shown by American academics David Freidel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker in their fabulous work Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path, published in 1993.

Moreover, Cygnus's location adjacent to the stars of Sagittarius and Scorpio, where the ecliptic (the path of the sun), crosses the Milky Way, makes it an important feature in the eschatological phenomenon associated with the birth of the new sun at the climax of the Maya Long Count calendar on 21 December 2012.

The sun will emerge at this time at a point that aligns with the visual position of galactic centre, something which some modern researchers feel the Maya were aware of somehow. In ancient Mexican cosmology, the sun was seen as an egg that comes from a crack which opens in a cosmic mountain, and this can be equated with the Milky Way's Great Rift, the dark region caused by interstellar dust clouds where new stars are born.

This begins at Cygnus and continues on down to Sagittarius and Scorpio, where it opens out to form the point of emergence of the new sun.

Back to Contents

vi. Pathway to the Gods

In Peru also, the pre-Conquest peoples of the Andes believed that the Milky Way was the celestial river leading to the sky-world, findings elegantly displayed in the writings of cultural historian William Sullivan. More curiously, they revered north as 'up', as well as the direction that features in their ancient cosmology.

This is despite the fact that Peru is in the Southern Hemisphere, and the northern celestial pole would not have been visible. At Cuzco, the administrative capital of the Inca Empire, the rebirth of the sun was celebrated at the time of the winter solstice (the summer solstice of the Northern Hemisphere). Here was to be found the sacred river known as the Vilcanota, seen as a terrestrial representation of the Milky Way.

All along the river valley are topographical features such as settlements, terraces and even cities built on prominent natural features that the Incas felt were terrestrial effigies reflecting the influence of star-to-star and dark cloud constellations located along the Milky Way.

Cuzco was seen by the Incas as the centre of the world, the axis mundi, linked to the sky-world via points of access on the Milky Way when it rose up from the horizon at the time of the solstices (just like at Newark's Great Circle).

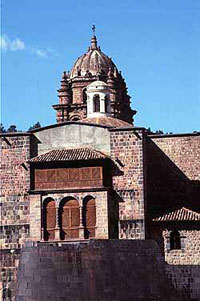

St Domingo church, Cuzco, built on the site of the Coricancha.

Cuzco's own terrestrial personification is that of a puma, the symbol of kay pacha, 'this world'. Its head and jagged teeth are to be seen at Sacsahuaman - the hilltop fortress famous for its foundation walls composed of breathtaking cyclopean masonry.

The town's main plaza of Huacaypata corresponds with the feline's belly and legs, while the Coricancha, site of the former temple of the sun on which was built the church of St Domingo, falls in the vicinity of its genitals.

The spine and tail of the puma are represented by the Tullumayu and Huatanay rivers, which flow into the Vilcanota river.

Italian astrophysicist Giulio Magli, Professor of Mathematical Physics at Milan's Politechnic, has identified Cuzco's celestial puma as a joint star-to-star and dark cloud constellation occupying the position of Cygnus at the very top of the Great Rift, demonstrating that this was the Incan point of access into the celestial abode, called hanaq pacha, the 'world above'.

It was here that the human soul started its life and would ultimately return in death. This was accessed, or linked, via its terrestrial counterpart focused upon Cuzco, the Incan centre of the world, making this place an expression of Cygnus laid out on the landscape.

Having satisfied ourselves that the associations between Cygnus, cosmic creation and the transmigration of the soul were once present throughout the American continent, and thus could have been imported from Asia as early as Palaeolithic times, we now cross the Atlantic and move closer to home in search of further clues to the Cygnus mystery.

Back to Contents

vii. The Winged Serpent

Prehistoric Avebury, the megalithic stone complex in the southern county of Wiltshire in South-west England, is second only to Stonehenge in grandeur and popularity.

Constructed c. 2600-2000 BC, it consists of a circular henge and ditch that appear uncannily like those making up Newark's Great Circle. Yet unlike its American counterpart, Avebury has a gigantic circle of standing stones inside the henge, with another pair of circles contained inside the larger one.

Approaching the great circular earthwork from a distance of around 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) were once two giant avenues of stones, of which only fragments of one remain today (the Kennet Avenue).

Aubrey Burl, a leading authority on megalithic structures in Britain, has outlined his belief that Avebury was the centre for a regional cult of the dead and rebirth.

Overhead photo of Avebury.

Avebury was surveyed during the eighteenth century by antiquarian William Stukeley, who saw the whole monument in terms of a winding serpent (the avenues) curling around a sun disk (the main henge and circles). For him it was a personification of Kneph, a Graeco-Egyptian creator god (also known as Chnoubis, or Khnum) which he acknowledged was linked in classical mysteries with the story of 'Cycnus', a character of legend personified in the sky as the Cygnus constellation.

Yet this fact was forgotten, even when in the 1960s Professor Alexander Thom, famous for finding stellar and lunar alignments at hundreds of stone circles across Britain, established that the central axis of Avebury was aligned to the setting of the star Deneb in Cygnus.

His contemporary Gerald Hawkins, author of the bestselling book STONEHENGE DECODED (1965), who famously used a computer to demonstrate that Stonehenge was used to calculate eclipses, doubted this, stating that the ancients would not have used such an insignificant star.

Yet what he did not know is that several other key megalithic sites in Britain are also aligned to Deneb, including a number of chambered monuments in the vicinity of Avebury. Was this a survival through from the Early Neolithic era, which had begun in Southeast Turkey some 7,000 years beforehand?

Adding to Avebury's suspected connections with the Cygnus constellation is the fact that the only carving to be seen on a standing stone there (Stone #25S in the Kennet Avenue) shows the head and neck of a swan (first identified by local earth mysteries writer John Wakefield). Nobody before had made the link between this stone and the swan.

In the knowledge that the water-filled meadows of nearby Silbury Hill, as well as the Kennet river which runs alongside Avebury, once played host each winter to flocks of migrating whooper swans inbound from their breeding grounds in the Arctic, this had to relate in some way to Avebury's axial alignment towards the setting of Deneb.

In the knowledge that Avebury has frequently been linked with the ancient British goddess called variously Bride, Brigid, Bridget, Breeshey and Brigantia, whose main totemic symbols are the swan and serpent, might she help us better define the precise nature of the site's link to Cygnus?

Back to Contents

viii. Goddess of the Swan

The Irish Brigid or Bridget, Scottish Bride, or Manx Bree, or Breeshey derive from a common root, a female deity who almost certainly served as the tutelary goddess for the first Iron Age peoples to enter Britain in the first millennium BC. Her cult lingered through until Romano-British times, most obviously as the divine patron of the Brigantes, the powerful northern tribe famously led at the time of the Roman conquest by the warrior queen Cartamandua.

With the arrival of Christianity Brigid became a saint, celebrated as Jesus's nursemaid, and sometimes even as his mother under the name 'Mary of the Gaels'. St Bride, or Bridget, bore an assortment of animal forms, but by far the most significant is that of the white swan. In her role as patron of childbirth, Bride-Bridget was associated with the Milky Way, where the celestial swan flies, and her mark was the bird's foot, anticipated by peoples of the Scottish Western Isles in their hearth on the morning of her feast day.

This same symbol was associated by Welsh bards and druids with the goddess Minerva, the given to the Gallic form of Brigantia, or Brigid, by the Romans. Yet what might any of this have to do with Avebury's cult of the dead?

A more direct association between swans and the northerly transmigration of the soul comes in the knowledge that in the Scottish Western Isles people saw whooper swans (and also greylag geese) migrating northwards to their breeding grounds in Iceland each spring as carrying the souls of the dead to heaven, which lay 'north beyond the north wind', an expression borrowed from classical mythology. Should a person be alive when the birds depart, then they would be free from death for another year.

Cygnus being essentially circumpolar in Scotland would always have been seen in the northern night sky. Is this how the stars of Cygnus became associated with the swan, and why the bird was linked with not only the cosmic axis, but also the journey of the soul into the afterlife - because it was seen to fly towards the celestial pole?

If so, then this connection can only have begun when Deneb occupied the position of Pole Star in c. 15,000 BC.

Swans in flight

Among the peoples of the Baltic the swan replaced the stork as the bringer of new-born babies, showing that it both brought life and took it away again.

This process of giving and taking life is exemplified at Çatal Huyuk in Southern-central Turkey where Neolithic wall sculptures contain vulture's skulls inserted horizontally so that the tips become the nipples of sculpted breasts, while murals nearby show human foetuses inside the bodies of vultures.

The cult of Bride-Bridget exemplified these archaic beliefs, and these survived through until the nineteenth century in the Scottish Western Isles. However, evidence of her worship in England has been scant until now. Yet archaeologists working in South-west England have recently unearthed macabre evidence of a pagan cult of the swan, possibly associated with the goddess Bride-Bridget, which survived through until the 1640s.

It comes in the form of a series of earthen pits unearthed at Saveock, Cornwall, and found to contain carcasses of swans, as well as other votive offerings such as eggs, down feathers, crystals and stones. It is important to recall that at this time England was under Puritan rule, with the punishment for any kind of sympathetic folk magic being very severe indeed.

In Britain, the cult of the swan is likely to have come under the protection of Bride, whose feast day, 1st February, marked the northern departure of the migrating swans.

Yet her worship proved to be only half the story, for a whole different cult of the swan once surrounded the return of the birds each November, a fact echoed in an archaic ceremony that continues each year on the River Thames.

Back to Contents

ix. The Waters of Life

The cult of the swan never died out in England, it simply transformed into something new.

For over 600 years, two ancient livery companies of London - the Vintners and Dyers - have accompanied the British sovereign's swan-master and swan-warden on an enchanting journey along the River Thames from London to Oxford. Its purpose is to mark and weigh all cygnets - young swans - allotted by birth-right to one or other of the companies.

Great pomp and ceremony surrounds Swan-upping, as the event is known, which takes place in the third week of July (previously in association with a swan feast on St Swithin's Day, 15 July). What is more, the Vintners - the wine traders - have a whole room celebrating Swan-upping at Vintners' Hall, their home close to the River Thames in the City of London.

The expression 'upping' refers both to the taking up of the young birds from the water, and to the magical journey itself, which halts at the lock closest to Windsor Castle in order that the swan-master might toast the reigning sovereign as 'Seignior of the Swan'.

Strangely, the whole event coincides with a major annual meteor shower called the Alpha Cygnids, where meteors are seen to come from Deneb in Cygnus, an astronomical firework display that could not have gone unnoticed.

Swan Upping on the Thames

Moreover, there is some evidence that the Vintners Company, derived from a 'mystery', or guild, of Saxon origin, was linked originally to the city's Roman Temple of Isis, which lay within 300 meters of Vintry Wharf, where the Swan-upping ceremony traditionally began.

Isis, the sister-wife of Osiris in Egyptian mythology, was the inventor of wine. Her symbol was traditionally the goose, although through classical associations in Roman times she became associated with the swan through her absorption of elements of the cult of Venus-Aphrodite. It is thus possible that Isis's followers in London might have honoured a pre-existing cult of the swan associated with the River Thames, where in London colonies of swans were a familiar sight right through until medieval times.

Another clue to the pagan origin of Swan-upping, and the mystery of the Vintners, is their patron St Martin of Tours. On his holy day (11 November) they performed a swan feast, during which a roasted swan was ceremoniously paraded around the banqueting room before being eagerly consumed by all present.

Although this tradition continues, today the Vintners eat a goose at Martinmas, while instead of a roast swan being paraded around its place is taken by a stuffed bird. When not in use, it is kept in the Swan Room at Vintners' Hall.

Christian tradition associates St Martin with geese, although the fact that geese were also once sacrificed on his feast day across Europe argues for a much older pagan origin for this ceremonial act. Indeed, there can be little doubt that Martinmas developed as an extension of the former pagan cross-quarter day of Samhain, the Celtic new year, known also as All Soul's Day, or the Day of the Dead.

It was around this time that migrating swans (and geese) returned from the Arctic, most usually at night under a full moon. Whooper swans in particular make unearthly sounds in flight that might once have been taken as the dead returning to this world, the origin perhaps of the association between Hallowe'en and the skies being alive with witches, spirits and other supernatural specters at this time (old pictures exist showing witches riding geese in particular).

As St Martin's Day marked the arrival of migrating swans and geese, St Bride's Day on 1-2 February marked their departure, carrying the souls of the newly dead towards a northerly placed heaven among the stars of Cygnus. It is for this reason that Bride, or Bridget, became so much associated with swans and the Milky Way, for she was almost certainly a personification of the Cygnus constellation.

Such information provides us with some understanding of the annual rituals that once might have taken place at prehistoric Avebury, which becomes Britain's premier site for the cult of the swan.

Yet it is across the Irish Sea in Ireland that we find what is arguably the British Isles' most significant link between Cygnus and the Neolithic world.

Back to Contents